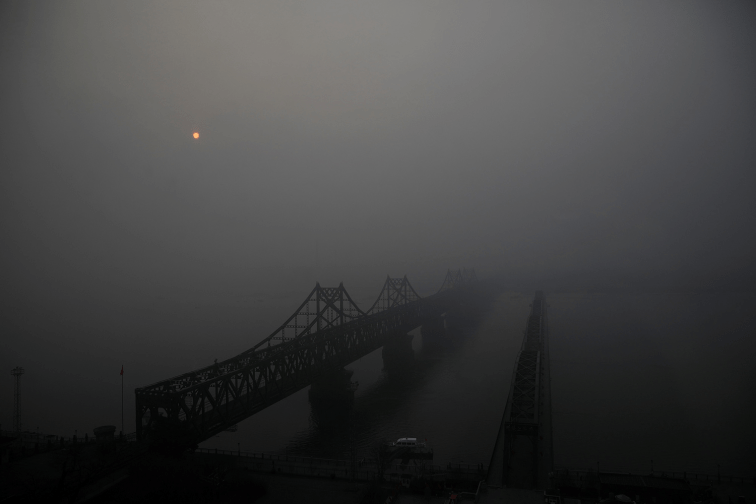

Let us survey the very visible and imaginable notion of conflict escalation on the Korean peninsula.

Any such conflict would at a minimum, encompass the full involvement of North Korea, South Korea, and American assets in the Pacific. Japan would likely be be involved in some capacity, Russia would most probably maneuver additional assets towards Asia, and the rest of the world would most definitely hold their breath as their collective gaze transfixes upon China. It is not that far of a stretch to surmise that Chinese involvement in the Koreas would be instrumental in deciding the outcome of any escalation, with ramifications that will certainly affect the world on an immense level.

If you are an individual who appreciates brevity in thought, allow for this quick summation of what a Chinese response would look like if current tensions surrounding North Korea were to quickly escalate into a greater conflict:

We don’t know for sure.

However, not knowing is not the same as not achieving a deeper understanding. To recognize and hopefully comprehend the logic behind China’s thought process, a further investigation beyond a curt answer is necessary. Not every question has an answer, but the very process of asking can provide a better grasp of the situation.

For the purpose of this investigation, a hypothetical – yet plausible – backdrop will be used as a starting point: North Korea’s advancements in intercontinental ballistic missile technology have quickly refined to the point of reaching across the Pacific¹, while the fiery rhetoric against the United States and its allies continues to remain dangerously aggressive. In understanding where China would stand in a such a highly volatile state of affairs, the critical points to be aware of are the asymmetrical nature of information and the credibility of Chinese commitment to North Korea. These are roadblocks in discussing what China can and would do because these very obstacles also hinder the ability of China’s own response strategy.

Consider the concept of war as a commodity that can be packaged and sold in numerous ways. Here are just some terms under which recent conflicts have transpired: humanitarian interventions, peacekeeping missions, and policing actions. In the modern age, wars have the luxury of not having to be declared anymore. This is not an assertion founded in cynicism; rather, it can be argued that this is a necessary development following the evolving lethality of armed conflict. By taking the war out of warfare, this gives belligerent powers both plausible deniability and the crucial ability to prevent a total escalation.

In the case of North Korea, therein lies another question. Just how far can the envelope be pushed before war is achieved? If the Trump administration were to not consider a preemptive strike on North Korean nuclear procurement facilities or missile silos as an act of war, then China would need to calculate that into how it responds to a potential American strike. On the flip side, how can the United States formulate a coherent policy on North Korea when the general understanding of what they consider to be an act of war is limited? Would a massive cyber attack on their network infrastructure be worthy of war? If not, what about limited or covert operations against specific targets? One must question what the threshold for war in this case is.

If one were to follow the general logic of a regime’s desire for self-preservation, it may be possible to estimate that very threshold – yet only to an extent. If a regime is unstable internally, the threshold may be lower since the state may be inclined to overreact given its internal problems. If a regime is more on the stable side, the threshold may be higher as it might be better equipped to respond to external actors. The caveat in all of this, however, is that North Korea is not a typical regime. There does not seem to be any hesitation to jump to proclamations of war, with official statements tending to be rife with apocalyptic imagery and threats to the American mainland. In addition, if a limited American strike effectively weakens or even disables North Korea’s ability to respond in kind (e.g. successfully dismantling their ability to strike long distances), North Korea could still pursue their response in the form of striking South Korean targets in their nearby vicinity. That, in turn, risks an escalation. Who would be at greater fault here? The United States for tossing the first rock? Or North Korea for repeatedly threatening to hurl their rocks?

In a sense, China has been cornered by its historical intentions to use North Korea as a buffer state. Instead of making things easier, the unchecked actions of a third generation dictator has threatened to pull China into a situation where they cannot confidently control. Attention may have been brought to China publicly stating and reaffirming its commitment to defending North Korea in the case of American aggression, but one would not expect China to communicate anything other than that. Additionally, public statements do not equate to private or classified beliefs, because to publicly state an intent of non-intervention to assist an ally is an implicit invitation for your ally (and the entirety of their strategic utility) to be destroyed. China may indeed have severe reservations regarding Kim Jong Un, but such qualms are necessary from China’s perspective to be withheld from overt public knowledge. Through the lens of classic power politics, abandoning allies very rarely gives one capital to use in a post-war environment – something that can be interpreted to be synonymous with the highly vaunted Chinese qualities of face and prestige. In short, China is stuck with using ambiguity to deter, rather than using assurance to de-escalate.

One can place themselves in the position of China by further assessing these aspects and conditions from a Chinese perspective:

- First, a study of both North Korean and American narratives of the attack: Do we have reason to believe escalation (and war) will continue, or do we believe it will be a limited strike with no follow-up? Does North Korea intend to respond in a manner beyond rational thought, or will they be forced to accept their losses?

- Secondly, an evaluation of prestige versus self-preservation: How do we decide to interpret an attack in both the context of our commitments and the context of our interests? Do our commitments align with the full spectrum of our interests?

- Finally, a projection of the end: Will our involvement lead to a desirable end to the conflict? And most of all, will our involvement put us in a position of strength and control?

Generally speaking, the modern leadership of the Chinese Communist Party has acted in a manner that denotes the characteristics of shrewd and risk-averse strategists. Yet while ideology has taken a backseat to the highly sought-after goals of stability and growth, escalation on the peninsula is something that cannot and will likely not be ignored. The greater the escalation, the more China will seek to be in the driver’s seat.

¹A task achievable within another year, according to US intelligence. “Intelligence Agencies Say North Korean Missile Could Reach U.S. in a Year”. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/us/politics/north-korea-missiles.html