It was the autumn of 1962. While much of the Western world was preoccupied with a missile crisis in the Caribbean, a brief war was waged along the rugged mountains of the Himalayas. The destinies of two future powers were briefly tested as they came head to head, and despite the outcome of a sound Chinese victory, it was apparent that both India and China were still at the mercy of the influence of forces greater than themselves – namely the superpowers of that period.

Fifty-five years later, China and India find themselves in a vastly different spot. Both nations are poised to be the grand forces of Asia in the coming decades, and if economic projections continue along their expected trends, both countries will be two of the world’s top superpowers by the middle of the century. This will almost certainly be the case, so long as their respective ascents into power remain competently led and harmoniously nurtured. However, obstacles and speed bumps remain a constant danger to each other’s progress. This is especially a danger if the two powers were to ever engage in conflict with each other.

On June 6th, a standoff between the Indian Army and the People’s Liberation Army began following an attempt by Chinese forces to construct a road. This appears to be an attempt to connect Yadong county in Tibet to the disputed plateau of Doklam (or Donglang in Mandarin). With the plateau being in a tri-junction where the borders of India, China and Bhutan connect, the Chinese claimed an old Indian military bunker obstructed the construction of the road. When India refused to accede to China’s request, the PLA forcibly removed the bunker using heavy machinery. Tensions immediately flared, and as of a month later, the standoff has continued with no resolute end in sight, marking it as the longest continuous standoff the two countries have had since the 1962 war. While there currently does not appear to be an overt risk of escalation, the situation has devolved into a war of words between the news outlets of both countries. With a few incendiary comments on the part of a second-tier Chinese mouthpiece (The Global Times) referencing the 1962 war, some worry if the standoff might threaten the diplomatic progress made between the two countries in recent years.

For cooler heads on both sides, it may be reassuring from their perspective that many important factors prevent a modern border spat from escalating, as the relationship between today’s India and China is significantly closer than the India and China of 1962. Both are considered to be integral BRIC economies; China stands as India’s largest trading partner in goods and services (not counting foreign direct investment), and India is the fourth largest trade partner that China holds a surplus with. In addition, India most recently joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization during its June summit in Kazakhstan, just a few days after the standoff in Doklam began. Last but certainly not least, both parties are nuclear powers, with nuclear weapons acting as the greatest inhibitor of any large-scale conventional escalation thanks to the terrifying prospects of mutually-assured destruction.

Because the two countries are so closely linked, one would expect this standoff to be seen as a trivial border spat in the long-term. However, such an attitude cannot be taken for granted. Even in a relationship where the actors involved can be considered to be highly rational and forward-thinking, outside factors have the potential to throw in unforeseen frustrations. As the notion of two nations being well on their way in becoming the leaders of a new global hegemon can be a cause of concern for other powers, the standoff in Doklam may be of particular interest for a nation that still occupies the number one spot in many categories – the United States of America.

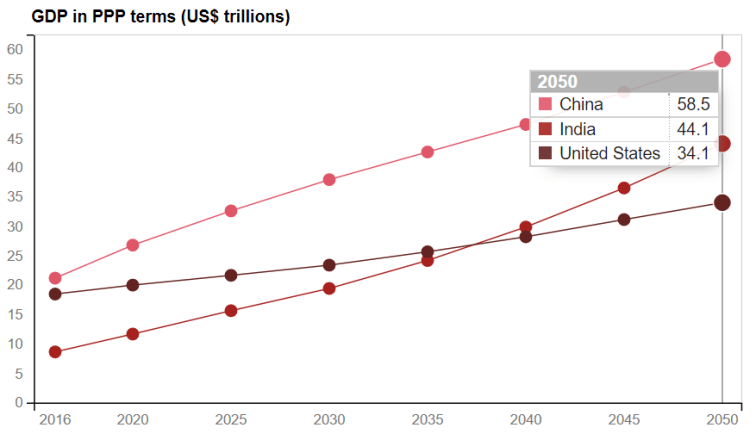

By the year 2050, the economies of China and India will stand as the first and second most powerful economies respectively (using GDP at PPP), according to projections by PricewaterhouseCoopers. Both countries will make up more than a third of the entire global population, and in essence, more than a third of the entire human race will be concentrated under the banner of two of the most powerful nations of that period.

The thing with growing superpowers is that their economies do not grow separately from other elements of power. The ability to project military might can be closely linked to the scale and quality of a country’s economic progress, and even in lieu of hard strength, a country’s increasing wealth allows for the ability to attract and co-opt through soft power. These elements are the basis for using a state’s economic clout to expand their regional hegemonies into a sphere of influence that spans the globe. Unlike ancient times where multiple empires could claim the top spot in their respective regions (like the Romans and the ancient Chinese), globalization has made today’s world one that is inextricably interconnected. As such, the rise of new powers have the absolute ability to surpass and overtake the previous leader of the global hegemon on many fronts. Furthermore, despite China’s close friendship and Pakistan and India’s embrace of the United States, there is a possibility that must be considered regarding the relationship between India and China. Together, they could easily hold an inordinate and gargantuan amount of power should they ever shift their national policies to being significantly closer with each other. A hypothetical Sino-Indian alliance of the future may very well stand as the most powerful political entity in human history.

This is not to say that the natural geopolitical advantages the United States has always possessed will be for moot (being situated in North America and having critical access to the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans), nor is it a claim that a harmonious relationship between the three nations cannot be achieved. Yet as an actor with a deeply vested interest in maintaining its prime standing and dominance, the United States has a definite stake in how the rise of India and China will turn out. Furthermore, those who benefit from an American hegemon – NATO and other US allies – may also prefer the balance of power to stay in the court of the United States (unless the negative ramifications of the Trump administration’s foreign policy approach are farther reaching than previously thought). There is an opportunity here for the United States to pursue, a potential from an American perspective to slow down the collective advance of India and China.

Even if the situation surrounding Doklam simmers and cools off, there is no better way for the United States to contain its present and future rivals by pitting them against each other in a mountainous region where direct American assets are considerably limited (one risk is its proximity to Pakistan and Afghanistan). A full out war between India and China would not be in the interests of any party (as it would devastate the global economy), yet the ramping up of tensions and distrust between to two, as well as forcing their respective militaries to divert more resources to each other, can be seen as beneficial to long-term American interests. This is especially the case if any further standoffs or conflicts are limited to their Himalayan borders, as conducting military activity in mountainous terrain require an inordinate amount of logistical resources to back up. The encouragement of limited and expensive engagements – just enough to nurture continuous anti-Chinese or anti-Indian sentiments against each other – is an avenue of strong potential from an American perspective. Even playing the role of a peacemaker on the surface would be a shrewd tactic to ensure any Sino-Indian conflict would not escalate involve the navies of the two countries, who have the ability to disrupt vital trade routes in the Indian Ocean, the Straits of Malacca, and the South China Sea to an extent should they ever engage each other at sea. Such a strategy might be seen as tremendously risky and unnecessary, especially with recent commitments by Trump and Modi to deepen ties between their countries. However, this is a prospect with implications that go far beyond the terms of the president and prime minister.

The prevention of rivaling power groups from linking up is the basis for the ancient principle of divide and conquer. From the perspective of elements within the United States that wish to uphold its hegemonic dominance, this may very well be pursued in the future in an attempt to maintain it. From the perspective of Beijing and New Delhi, cooler heads must prevail and key decision-makers must understand that while the two countries may have had bitter encounters in the past and present, they are far from unmendable. Most of all, they must be cognizant of the influence of outside parties that wish to see Sino-Indian relations remain tense.

(Images taken from The Indian Express, PwC, and CNN)